Philip Guston

Philip Guston | |

|---|---|

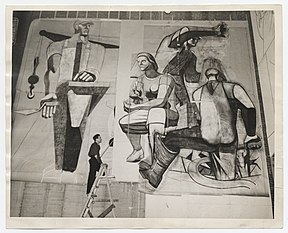

Guston in 1940 | |

| Born | Phillip Goldstein June 27, 1913 Montreal, Quebec, Canada |

| Died | June 7, 1980 (aged 66) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Los Angeles Manual Arts High School, Otis Art Institute |

| Known for | Painter, graphic artist, muralist, printmaker |

| Style | Cartoon, Abstract |

| Movement | Abstract expressionism, Neoexpressionism, figurative painting, New York School |

| Spouse | Musa McKim |

| Patron(s) | David McKee |

| Signature | |

Philip Guston (born Phillip Goldstein, June 27, 1913 – June 7, 1980) was a Canadian American painter, printmaker, muralist and draftsman. "Guston worked in a number of artistic modes, from Renaissance-inspired figuration to formally accomplished abstraction,"[1] and is now regarded as one of the "most important, powerful, and influential American painters of the last 100 years."[2] He frequently depicted racism, antisemitism, fascism and American identity, as well as—especially in his later most cartoonish and mocking work—the banality of evil. In 2013, Guston's painting To Fellini set an auction record at Christie's when it sold for $25.8 million.[3]

Guston was a founding figure in the mid-century New York School, which established New York as the new center of the global art world, and his work appeared in the famed Ninth Street Show and in the avant-garde art journal It is. A Magazine for Abstract Art. By the 1960s, Guston had renounced abstract expressionism and was helping pioneer a modified form of representational art known as neo-expressionism. "Calling American abstract art 'a lie' and 'a sham,' he pivoted to making paintings in a dark, figurative style, including satirical drawings of Richard Nixon" during the Vietnam War as well as several paintings of hooded Klansmen,[4] which Guston explained this way: "They are self-portraits … I perceive myself as being behind the hood … The idea of evil fascinated me … I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan."[5] The paintings of Klan figures were set to be part of an international retrospective sponsored by the National Gallery of Art, the Tate Modern, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 2020, but in late September, the museums jointly postponed the exhibition until 2024, "a time at which we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the center of Philip Guston's work can be more clearly interpreted."[4][6]

The announcement spurred an open letter, published online by The Brooklyn Rail and signed by more than 2,000 artists.[7][8] It criticizes the postponement and the museums' lack of courage to display or attempt to interpret Guston's work, as well as the museums' own "history of prejudice". It calls Guston's KKK themes a timely catalyst for a "reckoning" with cultural and institutional white supremacy, and argues that that is why the exhibition must proceed without delay.[8] On October 28, 2020, the museums announced earlier exhibition dates starting in 2022.[9]

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]The child of Ukrainian Jewish parents who escaped the persecution of pogroms by immigrating to Canada from Odessa, Guston was born in Montreal in 1913 and moved to Los Angeles in 1919.[7] The family were aware of the regular Ku Klux Klan activities against Jews and Blacks which were taking place across California.[10] In 1923, possibly owing to persecution or the difficulty of securing an income, his father hanged himself in the shed, and the young boy found the body.[11]

Guston's interest in drawing led his mother to enroll him in a correspondence course from the Cleveland School of Cartooning.[11] In 1927, at the age of 14, Guston began painting and enrolled in the Los Angeles Manual Arts High School, where he met Jackson Pollock, who became a lifelong friend.[7] The two studied under Frederick John de St. Vrain Schwankovsky and were introduced to European modern art, Eastern philosophy, theosophy and mystic literature. The pair later published a paper opposing the high school's emphasis on sports over art, which led to expulsions, although Pollock eventually returned and graduated.[12]

Apart from his high school education and a one-year scholarship at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles,[7] which left him dissatisfied, Guston remained a largely self-taught artist, influenced by, among others, the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico, whom Guston repeatedly acknowledged throughout his career. He died in 1980 at the age of 66, of a heart attack, in Woodstock, New York.[12]

Work

[edit]Political murals

[edit]As an early activist, in 1932, the 18-year-old Guston produced an indoor mural with the artist Reuben Kadish in an effort by the communist-affiliated John Reed Club of Los Angeles to raise money in support of the defendants in the Scottsboro Boys Trial, in which nine Black teenagers were falsely accused of a rape in Alabama and sentenced to death."[7] The mural was then defaced by local police forces, organized into violent anti-communist Red Squads.[7] The subsequent court ruling found no fault on the part of the L.A. police, even though irreversible damage was sustained to many works of art.

In 1934, Philip Goldstein (as Guston was then known)[13] and Kadish joined their friend the poet Jules Langsner on a trip to Mexico, where they were commissioned to paint a 1,000-square-foot (93 m2) mural on a wall in the former summer palace of the Emperor Maximilian in the state capital of Morelia. They produced the impressive The Struggle Against Terror, whose antifascist themes were clearly influenced by the work of David Siqueiros.[14] The mural "includes the hooded figures that became a lifelong symbol of bigotry for the artist."[7] A two-page review in Time magazine quoted Siqueiros's description of them: "the most promising painters in either the US or Mexico."[14] In Mexico he also met and spent time with Frida Kahlo and her husband Diego Rivera.[citation needed]

In 1934–35, Guston and Kadish also completed a mural that remains to this day at City of Hope Medical Center, a tuberculosis hospital at the time, located in Duarte, California.[citation needed]

WPA murals

[edit]In September 1935, aged 22, Guston moved to New York, where he worked as an artist in the WPA program during the Great Depression. In 1937, he married the artist and poet Musa McKim, whom he first met at Otis, and they collaborated on several WPA murals. During this period his work included strong references to Renaissance painters such as Piero della Francesca, Paolo Uccello, Masaccio, and Giotto. He was also influenced by American Regionalists and Mexican mural painters.[1] In 1938 he painted a post office mural in the US post office in Commerce, Georgia, entitled Early Mail Service and the Construction of Railroads, and in 1944, he completed a mural for the Social Security building in Washington, D.C.[citation needed]

Abstract expressionism

[edit]In the 1950s, Guston achieved success and renown as a first-generation abstract expressionist,[10] although he preferred the term New York School. During this period his paintings often consisted of blocks and masses of gestural strokes and marks of color floating within the picture plane, as seen in his painting Zone, 1953–1954. These works, with marks often grouped toward the center of the composition, recall the "plus and minus" compositions of Piet Mondrian or the late Nymphea canvases by Monet.

Guston used a relatively limited palette, favoring black and white, grays, blues and reds. It was a palette that would remain evident in his later work, despite Guston's attempts to expand his palette and reintroduce abstraction to his work late in life, as evidenced in some of his untitled work from 1980 that has more blues and yellows.

Neoexpressionism

[edit]In 1967, Guston moved to Woodstock, New York. He was increasingly frustrated with abstraction and began painting representationally again, but in a personal, cartoonish manner.[1] "It disappointed many when he returned to figuration with aplomb, painting mysterious images in which cartoonish-looking cups, heads, easels, and other visions were depicted against vacant beige backgrounds. People whispered behind his back: "He's out of his mind, and this isn't art," curator Michael Auping said. "He could have ruined his reputation, and some people said he did."[1] The first exhibition of these new figurative paintings, including The Studio, Blackboard, and City Limits, was held in 1970 at the Marlborough Gallery in New York.[15] It received scathing reviews from most of the art establishment.[1] Memorably, New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer ridiculed Guston's new style in an article entitled "A Mandarin Pretending to Be a Stumblebum",[16] referring to "mandarin" in the sense of an influential figure and "stumblebum" meaning a clumsy person.[16] He called the act of changing styles an "illusion" and an "artifice". The initial reaction of Robert Hughes, critic for Time magazine, who later changed his views, was put into a scathing review entitled "Ku Klux Komix".[17]

According to Musa Mayer's biography of her father in Night Studio, the painter Willem de Kooning was one of the few who instantly understood the importance of these paintings, telling Guston at the time that they were "about freedom."[18] Cherries III from 1976, held in the collection of the Honolulu Museum of Art, is an example of his late-style representational paintings. Although cherries are a mundane subject, their spiky stems can be a metaphor for the crudeness and brutality of modern life.[19]

As a result of the poor reception of his new figurative style, Guston isolated himself even more in Woodstock, far from the art world that had so utterly misunderstood his art.[10]

In 1960, at the peak of his activity as an abstractionist, Guston said, "There is something ridiculous and miserly in the myth we inherit from abstract art. That painting is autonomous, pure and for itself, therefore we habitually analyze its ingredients and define its limits. But painting is 'impure'. It is the adjustment of 'impurities' which forces its continuity. We are image-makers and image-ridden."[20] From 1968 onward, after moving away from abstraction, he created a lexicon of images such as Klansmen, light bulbs, shoes, cigarettes and clocks.[10] In late 2009, the McKee gallery, Guston's long-time dealer, mounted a show revealing that lexicon in 49 small oil paintings on panel painted between 1969 and 1972 that had never been publicly displayed.

A catalogue raisonné of the artist's work was compiled by the Guston Foundation in 2013, coinciding with recent scholarly interest that explored the periods he spent in Italy.[21]

Legacy

[edit]Public collections

[edit]- Art Institute of Chicago

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza Art Collection (Albany, NY)

- High Museum of Art

- Honolulu Museum of Art,[19]

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

- Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

- National Gallery of Art

- Tate Modern

- Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

In 2022, Guston's daughter, Musa Mayer, gifted 96 paintings and 124 drawings from her personal collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art; this acquisition of more than 200 pieces is the largest collection of Guston's work held by a single institution.[22]

Academic affiliations

[edit]Guston was a lecturer and teacher at a number of universities, and served as an artist-in-residence at the School of Art and Art History at the University of Iowa[23] from 1941 to 1945. He then served an artist-in-residence at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri until 1947. He continued with his teaching at New York University and at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and, from 1973 to 1978, he conducted a monthly graduate seminar at Boston University.[24]

Among Guston's students were two graduates of the University of Iowa, painters Stephen Greene (1917–1999)[25] and Fridtjof Schroder (1917–1990),[26] as well as Ken Kerslake (1930–2007), who attended the Pratt Institute. Rosemary Zwick was a student at Iowa.[27] Among those who attended his graduate seminars at Boston University were painter Gary Komarin (1951–),[28] sculptor and painter Susan Mastrangelo (1951–)[29] and new media artist Christina McPhee (1954–).[30]

He was also posthumously elected to the National Academy of Design as an Associate Academician.

2020 controversy

[edit]In the fall of 2020, Philip Guston Now, a long-planned traveling retrospective of Guston's work, which included 24 of the Klan paintings,[4] was postponed until 2024 by the traveling show's four sponsoring institutions: the National Gallery of Art; the Tate Modern; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.[31][32] In a joint press release issued by the museums, they wrote: "The racial justice movement that started in the U.S. and radiated to countries around the world, in addition to challenges of a global health crisis, have led us to pause," explaining that the international tour, which had already been rescheduled because of the coronavirus, was best delayed "until a time at which we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice … can be more clearly interpreted."[2][6] Public response led to a "deluge of criticism from inside the art world,"[4] as well as major articles in New York magazine, The New York Times, CNN, Artforum, Tablet, and The Wall Street Journal, among other publications.

The most scathing response was collective, and organized in an open letter published online by The Brooklyn Rail. The letter featured a "list of signatories [that] reads like a roll call of the most accomplished American artists alive: old and young, white and Black, local and expat, painters and otherwise,"[32] including Matthew Barney, Nicole Eisenman, Charles Gaines, Ellen Gallagher, Wade Guyton, Rachel Harrison, Joan Jonas, Julie Mehretu, Adrian Piper, Pope.L, Martin Puryear, Amy Sillman, Lorna Simpson, Henry Taylor, and Christopher Williams. Strongly criticizing the museums' lack of courage to display the work, attempt to interpret it, or come to terms with the institutions' own "history of prejudice", the signers unanimously described the exhibition as a timely prompt for a "reckoning" — adding that that was why it must proceed as scheduled.[33] As of October 3, 2020, more than 2,000 artists[7] had signed the letter, but the exhibition organizers did not respond until they rescheduled the exhibition for dates beginning in 2022.[9] Philip Guston Now opened at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston on May 1, 2022.[34]

Popular culture

[edit]In "Cat and Girl versus Contemporary Art," part of the Cat and Girl webcomic series, author Dorothy Gambrell critiques the difficulty and purpose of finding the meaning behind art using Guston's iconic Head and Bottle painting.[35]

Auction record

[edit]In May 2013, Christie's set an auction record for the artist's work To Fellini, which sold for US$25.8 million.[3]

See also

[edit]- Boston Expressionism

- Max Beckmann

- Morton Feldman – the composer frequently drew inspiration from Guston's abstract expressionist work (including in the four-hour chamber composition For Philip Guston)[36]

- Red Grooms

- Claes Oldenburg

- Jean Dubuffet

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Greenberger, Alex (September 30, 2020). "Philip Guston's KKK Paintings: Why an Abstract Painter Returned to Figuration to Confront Racism". Artnews.

- ^ a b Saltz, Jerry (October 1, 2020). "4 Museums Decided This Work Shouldn't Be Shown. They're Both Right and Wrong. Fear postponed a Philip Guston retrospective. A reckoning must follow". New York Magazine.

- ^ a b "AUCTION RESULTS: CHRISTIE'S CONTEMPORARY EVENING SALE". Artobserved. May 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Jacobs, Julia and Jason Farago (September 25, 2020). "Delay of Philip Guston Retrospective Divides the Art World". New York Times.

- ^ "Sense or censorship? Row over Klan images in Tate's postponed show". the Guardian. September 27, 2020. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ^ a b "Philip Guston Now". www.nga.gov. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schwendener, Martha (October 2, 2020). "Why Philip Guston Can Still Provoke Such Furor, and Passion". New York Times.

- ^ a b "Open Letter: On Philip Guston Now". Google Docs. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ a b "Postponed Philip Guston Retrospective to Open in 2022". Artforum. November 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Marmer, Jake (October 2, 2020). "The Artist Formerly Known as Guston". Tablet.

- ^ a b "Philip Guston". May 9, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ a b "Philip Guston | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart.si.edu. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ^ Aaron Rosen, Imagining Jewish Art: Encounters with the Masters in Chagall, Guston, and Kitaj (MHRA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-906540-54-8), p. 50: "In the mid-1930s the artist began, off and on, to use the surname 'Guston' in place of his inherited name of 'Goldstein'".

- ^ a b Boime, Al (2008). "Breaking Open the Wall: The Morelia Mural of Guston, Kadish and Langsner". The Burlington Magazine. 150 (1264): 452–459. JSTOR 40479800.

- ^ "Philip Guston". www.gustoncrllc.org. The Guston Foundation. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Kramer, Hilton (October 25, 1970). "A Mandarin Pretending To Be A Stumblebum". The New York Times.

- ^ Hughes, Robert (November 9, 1970). "Art: Ku Klux Komix". Time – via content.time.com.

- ^ Mayer, Musa, Night Studio (Da Capo Press, 1997), p. 157

- ^ a b Honolulu Museum of Art, wall label, Cherries III by Philip Guston, 1976, oil on canvas, accession 7008.1

- ^ Balken, Debra Bricker; Philip, Guston; Berkson, Bill (1994). Philip Guston's poem-pictures. University of Michigan: Addison Gallery of American Art. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-879886-38-4.

- ^ "Features – American Academy in Rome". www.aarome.org.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (December 14, 2022). "More Than 200 Philip Guston Works Are Headed to the Met". The New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ Brookman, Christopher from Grove Art online, http://www.moma.org/collection Accessed June 27, 2009

- ^ http://www.themorgan.org/about/press.GustonChronology.pdf[permanent dead link] Accessed June 27, 2009

- ^ Smith, Roberta, "Stephen Greene, 82, 'Painter with Distinctive Abstract Style'" November 29, 1999, Obituaries, The New York Times

- ^ Luther College Fine Art Collection, http://finearts.luther.edu/named_collections/schroder.html Accessed June 27, 2009

- ^ Jules Heller; Nancy G. Heller (December 19, 2013). North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century: A Biographical Dictionary. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-63882-5.

- ^ Diehl, Carol, "Gary Komarin at Spanierman Gallery", May 2008, Art in America

- ^ Nelson, Jennifer. "Painting With Fabric and Knits: Interview with Susan Mastrangelo," The Woven Tale Press, July 13, 2022. Retrieved June 13, 2023.

- ^ "Christina McPhee | Biography". Archived from the original on June 29, 2009. Retrieved May 27, 2010. Accessed June 27, 2009

- ^ Holland, Oscar (October 1, 2020). "Artists slam decision to postpone exhibition of Philip Guston's KKK paintings". CNN.

- ^ a b Farago, Jason (September 30, 2020). "The Philip Guston Show Should Be Reinstated". New York Times.

- ^ The Brooklyn Rail. "Open Letter: On Philip Guston Now". The Brooklyn Rail's Google Docs site for the publication of the open letter.

- ^ Whyte, Murray (May 1, 2022). "The MFA recast artist Philip Guston amid a nationwide racial reckoning — here's the result". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- ^ "Cat and Girl » Archive » Cat and Girl versus Contemporary Art". catandgirl.com. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ Bernard, JW (2002). "Chapter 7: Feldman's painters". In Johnson, S (ed.). The New York schools of music and visual arts: John Cage, Morton Feldman, Edgard Varèse, Willem De Kooning, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg. New York: Routledge. pp. 203–204. ISBN 978-0-8153-3364-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Arnason, H. Harvard. Philip Guston. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1962.

- Auping, Michael. Philip Guston: Retrospective (Thames & Hudson, 2006). ISBN 978-0-500-28422-3

- Botelho, Manuel. Guston em contexto: até ao regresso da figura. Lisbon: Livros Vendaval, 2007. ISBN 978-972-8984-05-2

- Bucklow, Christopher. What is in the Dwat. The Universe of Guston's Final Decade (The Wordsworth Trust, 2007) ISBN 978-1-905256-21-1

- Burnett, Craig. Philip Guston: The Studio. (London and Cambridge, MA: Afterall Books / MIT Press, 2014)

- Coolidge, Clark. Baffling Means: Writings/Drawings (Stockbridge, MA: O-blek Editions, 1991).

- Corbett, William. Philip Guston's Late Work: A Memoir (Cambridge, MA: Zoland Books, 1994)

- Feld, Ross. Guston in Time: Remembering Philip Guston (Counterpoint Press, 2003) ISBN 978-1-58243-284-7

- Mayer, Musa. Night Studio: A Memoir of Philip Guston (originally published: New York: Knopf, 1988; new edition: Da Capo Press, 1997) ISBN 978-0-306-80767-1

- Marika Herskovic, New York School Abstract Expressionists Artists Choice by Artists, Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (New York School Press, 2000.) ISBN 978-0-9677994-0-7. p. 18; p. 37; p. 170–173

- Marika Herskovic, American Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s An Illustrated Survey, Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (New York School Press, 2003.) ISBN 978-0-9677994-1-4. p. 150–153

- Marika Herskovic, American Abstract and Figurative Expressionism Style Is Timely Art Is Timeless An Illustrated Survey With Artists' Statements, Artwork and Biographies. (New York School Press, 2009.) ISBN 978-0-9677994-2-1. p. 112–115; p. 136

- Dore Ashton, A Critical History of Philip Guston, 1976

- Yale University Art Gallery, Joanna Weber and Harry Cooper. Philip Guston, a New Alphabet, the Late Transition, 2000, ISBN 978-0-89467-085-5

- Robert Storr, Guston, Abbeville Press, Modern Masters, ISBN 978-0-89659-665-8, 1986

- David Kaufmann, Telling Stories: Philip Guston's Later Works (University of California Press, 2010) ISBN 978-0-520-26576-9

- Peter Benson Miller, ed. Philip Guston, Roma ex. cat. with texts by Peter Benson Miller, Dore Ashton, Musa McKim and Michael Semff (Hatje Cantz, 2010) ISBN 978-3-7757-2632-0

- Peter Benson Miller, ed. Go Figure! New Perspectives on Guston, 2015 ISBN 978-1-59017-878-2

- Michael Semff, 'An Unknown Lithograph from Philip Guston's Late Work,' Print Quarterly, XXVIII, 2011, 462–64

- 'Philip Guston: Prints', Catalogue Raisonné, Text by Michael Semff, English, Sieveking Verlag 2015, ISBN 978-3-944874-18-0

- 'Philip Guston: Drawings for Poets', Foreword by Michael Krüger, Text by Bill Berkson, English, Sieveking Verlag 2015, ISBN 978-3-944874-19-7

- Zaller, Robert (1998). "The late iconography of Philip Guston" (PDF). Apodemon Epos: Magazine of European Art Center (EUARCE) of Greece (5): 4.

- Cooper, Harry; Godfrey, Mark Benjamin; Nesin, Kate; Greene, Alison de Lima (2020). Philip Guston Now. Washington: National gallery of art. ISBN 978-1-942884-56-9.

- Guston, Philip (2020). Poor Richard by Philip Guston. Washington: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-1-942884-57-6.

External links

[edit]- The Guston Foundation

- Philip Guston artwork at Brooke Alexander Gallery

- Works by Philip Guston and related exhibition records at the Museum of Modern Art in New York

- Biography of Philip Guston by Christopher Brookeman, Grove Art Online, 2007 Oxford University Press

- Philip Guston at McKee Gallery at McKee Gallery, New York

- Philip Guston: A Life Lived (1982) – Film about his life

- Conversations with Philip Guston – Film by Michael Blackwood

- 20th-century American painters

- American male painters

- 20th-century Canadian painters

- Canadian male painters

- Abstract expressionist artists

- American abstract artists

- American contemporary painters

- American muralists

- Anglophone Quebec people

- Modern painters

- 1913 births

- 1980 deaths

- Canadian emigrants to the United States

- Canadian people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent

- Jewish American painters

- Jewish Canadian artists

- Artists from Montreal

- Art Students League of New York faculty

- Washington University in St. Louis faculty

- Otis College of Art and Design alumni

- People from Woodstock, New York

- Federal Art Project artists

- 20th-century American printmakers

- Neo-expressionist artists

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- American satirists

- Canadian satirists